OSKAR JOHANSON

THANK YOU ❤️ FREMANTLE read the banner flying from the rear of the MV Artania, a parting shot of kindness aimed at a city desperate to see the ship go. For weeks, the 44,000-tonne cruise liner had sat in the docks of the Western Australian city, refusing to depart, its captain wary of taking to sea with potential cases of the coronavirus on board. But now, with a clean bill of health, it was preparing to leave. Its final destination would be the German coast, from which it had set sail in late 2019, before the pandemic, another universe away. But before it could make for Europe, the Artania was going to do something few cruise liners had ever done before.

1

At the outset of the pandemic, cruise liners seemed somehow more culpable than any other kind of vessel for spreading the new SARS-CoV-2 strain of coronavirus. Off all the world’s coasts they lurked, denied entry to ports one after another; their multi-ethnic, precariously employed crews directly implicated not only in on-board cases but every subsequent infection on land as well. Notoriously tacky and dirty, cruise liners had long been associated with disease, such as norovirus. It was comforting to think that they were uniquely primed for such an outbreak — perhaps even deservingly so.

Yet, examination of the cruise liner reveals that the failure to control coronavirus on these vessels was — indeed, could only have been — precipitated and then followed by similar failures on land. Like many other ocean-going vessels, a cruise liner must always exist in relation to an outside: the rules that govern it are written on land; the owners of it live on land; and the membrane that cleaves it from the shore when it is docked is often a porous one. These tensions usually remain hidden, but under the pressure of the pandemic they not only came under scrutiny but threatened to invert or collapse entirely.

An enduring model for thinking through vessels in this sense remains Michel Foucault’s concept of heterotopia1. Developed through a series of sometimes contradictory texts, heterotopia was an idea with which to understand the particular conditions of our time: "simultaneity", "juxtaposition", "the near and far", "the side-by-side", and 'the dispersed’ — in other words, particular kinds of relations. By way of example, Foucault singled out one "extraordinary bundle" of such relations in the train,

“[...] because it is something through which one goes, it is also something by means of which one can go from one point to another, and then it is also something that goes by.” 2

2

Of particular concern to Foucault were "sites" that had "the curious property of being in relation with all the other sites, [...] in such a way as to suspect, neutralize, or invert the set of relations that they happen to designate, mirror, or reflect"3. Foucault argued that these sites fell into one of two broad categories: utopias and heterotopias. Utopias were sites that did not exist, and which could never exist, the concept playing on the origin of the word as ‘no place’. By contrast, heterotopias were sites that did exist in the real world, existing as ‘other/different’ (hetero) in relation to a wider milieu. If a utopia was a vision for an ideal society, given integrity only by the utterances of an idealist, or the boundaries of the plan of an architect, a heterotopia might be the real-world residue of a utopian project as it had actually been realized. Both could act upon the world, but only the latter could be inhabited.

In Foucault’s model, a heterotopia could be a repository for ‘slices’ of time4 – artifacts, ideas, customs, and rituals that belong to ages past or those yet to arrive. Conversely, if the norms and values of a community within such a site remained constant, but those outside changed over time, the result was also a heterotopia. Through a sometimes-permeable membrane, a heterotopia could delineate itself from, and control its material exchange with, an outside; and it was exactly such a membrane that allowed a heterotopia to contain a multitude of spaces, reproducing the outside world in miniature within, calling into question the status quo or suggesting a society anew.

In a beguiling concluding passage, Foucault claims that one type of space distills more clearly than any other the essence of heterotopia — the ship. And it is obvious that ocean-going vessels, cruise liners included, exhibit many of the qualities of heterotopia. Yet the value in thinking through the vessel-as-heterotopia is not limited to cruise liners, or to ships, or even to the sea at all. After all, for two years, the prevailing condition of our time has remained containment: hotel quarantine, city lockdowns, border closures, school closures, working from home — all measures to contain the body, to localize the ‘power of contagion’5. The obverse condition is containment failure: workplaces without adequate protection, the foregoing of health checks or safety protocols in the name of civil liberty or ‘business’, Rapunzelesque quarantine hotel escapes6. Ours is still an age of the near and far, and the side-by-side. But it is also the age of the held apart, the exclusively mediated, the indefinitely suspended. Ours is an age of vessels.

3

At the beginning of the twentieth century, it was the cruise liner’s direct antecedent, the ocean liner, that dominated world transport and communication. It was through the ocean liner that the cordons of empire were worked, cables laid, and settlers moved to the colonies. But liner business was seriously disrupted by the shutdown of mass migration to the US in the 1920s and terminally superseded by the jet engine in the 1950s. In response to these crises, cruises — voyages of pleasure in the shape of a loop or an open line — emerged as a way to keep excess tonnage profitable.

Visions of this ancestral age, badly remembered, are critical to the contemporary cruise imaginary. Cruise bookings soared following James Cameron’s stupendously lucrative Titanic, while Disney Cruise Line (DCL) vessels unapologetically plunder the colors and forms of Golden Age liners7. These fantasies build directly on the propaganda shipping lines developed during the heyday of the original liners themselves. Posters of Cunard Line in the 1920s, for example, regularly made use of a cross-section of a liner, the cut showing a dizzying, esoteric array of spaces, stacked one on top of another. In these images, labor is almost expunged, the sea is calm and mastered, the ship’s spaces of propulsion impressive but far from the dangerous inferno worked exclusively by people of color they almost certainly would have been. The posters embodied not the promise of a passage across the Atlantic (although this would be a happy side effect), but rather the chance to immerse oneself in a complex but stable landscape contained entirely within the thin steel membrane of the ship’s hull; a counter-world, distinct from the larger world of flux outside.

Advertising was in this regard far behind fiction. Jules Verne, Herman Melville, Joseph Conrad, and Katherine Anne Porter each understood that a vessel easily stands in for another vessel. The ship as a body, as a city, as a street, as a kingdom, as a moon, as the Earth — sometimes, paradoxically, all at once. Cunard’s posters were anticipated by centuries by Jonathan Swift’s Laputa and by decades by Jules Verne’s "Standard Island", the latter a mechanical, motile island inhabited exclusively by millionaires, though, in contrast to the poster, knowingly deployed as satire. In this critical sense, these stories built upon even earlier vessels of fiction deployed as satire: Brandt’s Ship of Fools; More’s Utopia.

Like its ancestral heterotopias, the contemporary cruise liner must fulfil its promise of consistent passenger comfort through a stupefying array of spaces and crew, hardcore machinery, and locally-generated myth, but it departs in several key ways. One difference is size. The Oasis of the Seas, one of the largest of all cruise liners and five times the gross tonnage of Titanic, deploys more than 250 chefs to transform more than 100 tonnes of food into 250,000 meals every 7 days — all of it stored as raw ingredients, turned into meals, and then turned again into sewerage entirely within the confines of the vessel8. Its fuel tanks can hold 15 million liters of fuel, with which it can move itself, generate its own electricity and therefore turn seawater into freshwater through desalination plants9. Another key difference is the shape of the global network of supplies and labor required to upkeep this system. The fate of a cruise liner depends not on immigration but by the shape of twenty-first century tourism and the myriad other concerns of corporate capital. The cruise liner is not the flagship of an imperial nation-state but a corporate asset: it works when customer demand is high; it is sent to be dismantled by laborers on the shores of Izmir or Chittagong the moment the market turns down10.

Yet, just like their forebears, the cruise liner’s itinerancy means that its relationship to the land necessarily changes. This can be because of spatial and juridical variances between one port and another, but it can just as well be because the same ports are themselves in constant flux. No ship truly returns to exactly the same city twice. This fact was demonstrated vividly by the case of MV Artania.

4

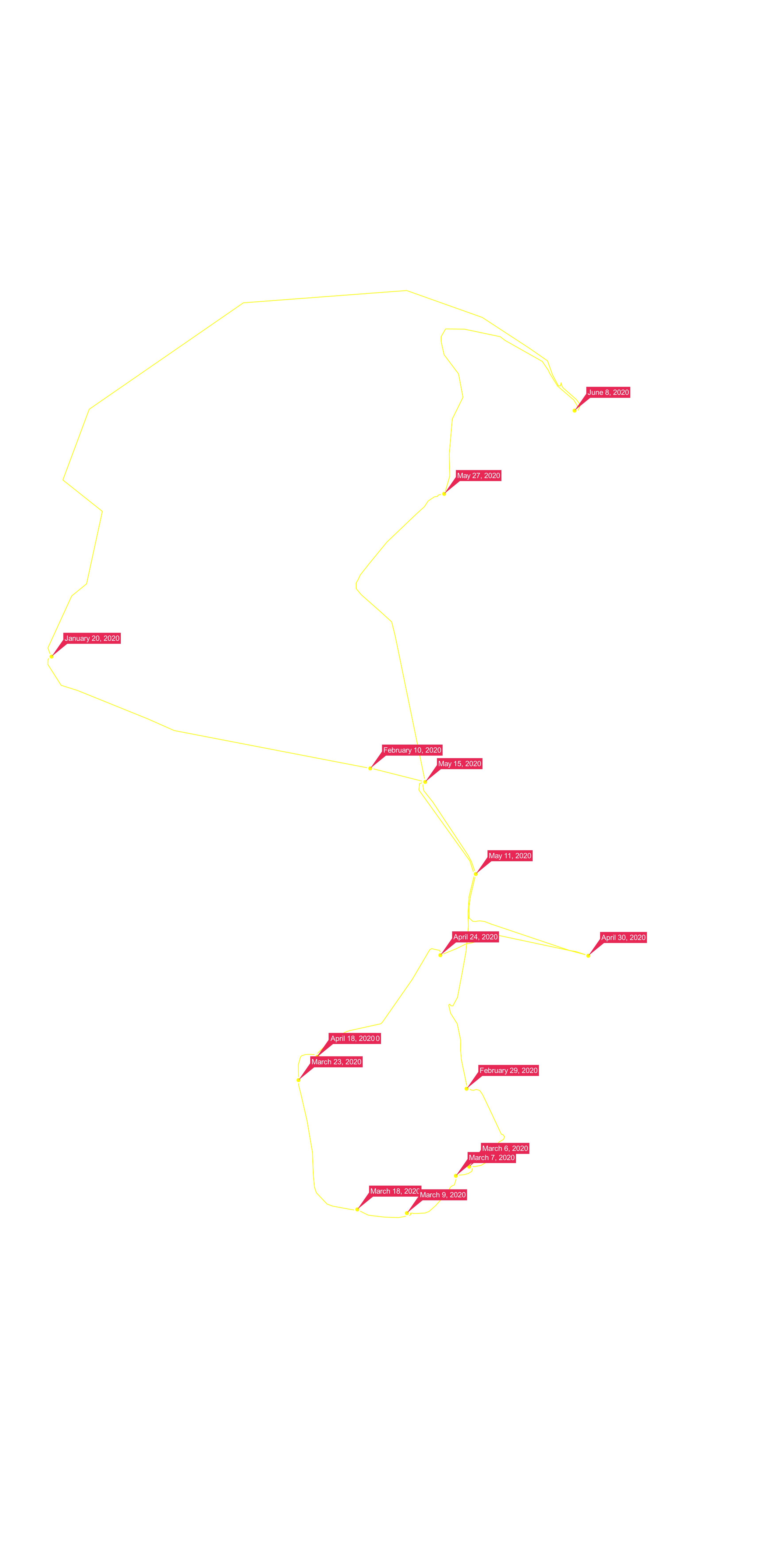

The Artania’s odyssey began on December 21, 2019 when the vessel departed Hamburg for a 140-day World Tour. It called in to London before heading south through the Atlantic, calling in at Ascension Island, St Helena, and Namibia, before rounding the Cape of Good Hope and heading north-east across the Indian Ocean. By February, port calls in South-East Asia had begun to disappear from the itinerary amid news of a dangerous virus that had emerged in China.

On March 11, the Artania was sailing down the east coast of Australia, somewhere between Brisbane and Sydney when, in Geneva, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic11. A week later it left Sydney, minus 200 of its most cautious passengers. A few days later, the Artania had rounded the continent’s south-eastern corner and was headed west across the Great Australian Bight, the sunny world on board now increasingly at odds with the land, where more and more cases of COVID-19 were being reported daily. Like Foucault’s vision of the train, the ship was now a ‘bundle of relations’ in a particular relation of difference to the shore; a moving slice of the last, halcyon days of 2019. It was a differentiation that could not last.

On March 23, 7 passengers on board tested positive for COVID-19. The vessel radioed officials in Fremantle, Western Australia asking for permission to dock and disembark its passengers. Fearing an outbreak, health officials refused the vessel’s request and instructed it to remain at sea; Western Australia’s premier suggested using the navy to keep it there. But by March 27, health officials had decided to allow the ship to dock under strict controls. Before the end of the month, most passengers had been disembarked. Those with symptoms were taken to hospital for treatment; after isolation, most other passengers were flown home. The vessel’s crew, on the other hand, remained on board, isolating.

By April 7, the ship was still in dock, refusing the demands of state officials for it to leave. The ship had been paralysed by the fear that it could return to the open sea with sick crew and not be so lucky finding another berth. Two passengers had now died of COVID-19 in hospital. But by April 18, satisfied its cases were under control, the ship prepared to leave, unveiling its banners of tactical gratitude. On board was a small group of elderly passengers who had opted to take their chances on the ship rather than fly. If they’d cared to look, they would have seen the captain officiating the wedding of two crew members on the wharf. The Artania had already once left behind the world in a state that was never to return. To wed now probably seemed as good a time as any.

Charter flights had been arranged to take its European crew home direct from Fremantle; not so for their South-East Asian colleagues. Instead, perhaps uniquely in the history of liners, the Artania began to visit the homeports of its crew itself. The vessel sailed from Fremantle to the Port of Tanjung Priok, Jakarta, where it disembarked its Indonesian crew. The vessel then sailed to Manila, where it disembarked its Filipino crew. In this way, the Artania had exchanged its itinerary of tourism for one of labor. Unable (or unwilling) to fly the crew of South-East Asian nations home, the vessel’s owner effectively collapsed what would have otherwise been the divergent vectors of worker and tourist into a single line, sketched haphazardly across the World Ocean.

After Manila, the vessel began the journey back to Europe, detouring on May 11 to sail in the shape of a love heart to celebrate Mother’s Day, a message that can still be read in historic ship tracking data. By May 27, the Artania exited the Suez Canal; on June 8, it reached Bremerhaven, 6 months after it had first left. With its frail passenger rump on board, it was the last cruise liner in service on the planet.

5

Like many other cruises, and the ocean liners that preceded them, the Artania was sold as a kind of utopia. This utopia was in fact a double utopia, requiring the contrivance of two worlds to work: the ship interior, unmolested by terrestrial contingency and whose internal workings remained hidden; and the outer world, compressed and abstracted into pure itinerary, a chain of places that exist only to be visited, or viewed from the balcony. The cruise liner in this way is a cinematic device, spinning utopian representations of both itself and the world, flat and in sequence.

After Foucault, we know that the places to which these utopian visions point are, in fact, no place. There are no cruise liners without labor, no beaches that can be visited without contamination, no private islands that do not require mass dredging. To the extent the world can be flattened into montage, it is an effect made possible only by corporate muscle and the complicity of the passenger. To engage with the cruise liner critically we must instead recognise it as heterotopia, defined fundamentally by its relation to the land, its wider mileu; subject to the avarice of its owners, the willingness of terrestrial officials to do their duty, the whim of politicians, and a thousand unseen ribbons of law. This much was made all the more obvious when the pandemic descended upon the Artania. Despite its operator’s claims that passengers would be ‘spoiled’ and sail in ‘modern luxury’, the ship was ultimately unsuited to protecting them; a fact not lost on the 200 people who left the ship in Sydney at the first sign of pandemic.

The detection of cases on board the Artania did more than end a slice of pre-pandemic European time that had been maintained, as if in aspic, by the machinery of the vessel. It revealed the contours of class and privilege that had been there the entire time. The vessel’s passenger list was overwhelmingly German, yet the vessel relied heavily on South-East Asian labor, a fact that reveals something of the wider geographic distribution of the maritime working class, and one with which the Artania had to eventually, physically, engage. By bringing the lifeworld of its South-East Asian crew into the ports of their home countries, the Artania subverted, for a brief moment in time, the very model of labor that exists in a cruise ship, in which a middle class public sees only a contiguous territory of service and leisure, while the infrastructure and precariously employed laborers that make it run are kept unseen. This is an exaggerated version of arrangements found everywhere on land as well, from hotels, restaurants, and retail complexes that pride themselves on the invisibility of all labor except wait staff and security, to mixed-tenure housing complexes that dictate separate entrances according to status. The subversion of this model came from making visible the threads that bound it to the land, invalidating the utopia of a labourless space, or of a leisure-world that could be kept distinct from the world of labor, revealing instead the heterotopic relation the ship had always had with both itself and its outside. Where in March it had held on to a slab of the past, in April the Artania now sailed with a future slice of time within it, a future in which a vessel existed in a fundamentally different relation to its crew and its outside, a future of one small part of the world as it could be.

It is in these ways that the story of one cruise liner, one kind of vessel, can begin to stand in for other vessels, and for other, non-ship, non-maritime spaces that we perhaps more clearly ought to recognise as vessels: the bedroom, the office, the train, our body. Each of these vessels exists in relation to an outside, which may have gone unnoticed, or whose exact contours may have been unexamined until now. The Artania’s accidentally radical, briefly-lived model is only one of the more illuminating examples of how, post-pandemic, we might re-order the relations of our world.

Footnotes

1︎︎︎ Heterotopia was first explicated by Foucault in the preface to “The Order of Things”, in which it describes a linguistic concept, and then returned to a year later, in a lecture given by Foucault in 1967, in which it is deployed in an explicitly spatial sense — and the sense in which I use it here. Although the term itself was ultimately abandoned by Foucault, however, echoes of the concept — in particular, its core concern with what Foucault called the ‘fatal intersection of time with space’ — are present throughout his work. See also commentary by Edward Soja (Soja 18-19) and Anthony Vidler (Vidler 18-22).

2︎︎︎ Foucault, Michel. The Order of Things: An archaeology of the human sciences. Routledge. 2002. pp.23-24.

3︎︎︎ Foucault, Of Other Spaces, pp.24.

4 ︎︎︎ Ibidem. p.26.

5︎︎︎ Foucault, The Order of Things, p.xvii.

6︎︎︎ Menagh, Joanna.

7︎︎︎ Johanson, Oskar.

8︎︎︎ “The World's Biggest Cruise Ship”.

9︎︎︎ Based on an estimate by NOAA: https://response.restoration.noaa.gov/about/media/how-much-oil-ship.html

10︎︎︎ See, for example, the images of Carnival cruise liners driven on to the shore of Izmir in 2020 following the collapse of the cruise market as a result of the pandemic.

11︎︎︎ WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020.

images

fig.1︎︎︎ Location data of the Artania while moored in Fremantle during April, 2020. The area represented is 3 metres square. Derived from data from the Australian Maritime Safety Authority [under Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 Australia License]. © AMSA 2013.

fig.2 ︎︎︎ The voyage of the Artania from northern Europe, around Africa, to Australia, and back again via the Suez Canal, between December 2019 and June 2020. Voyage path determined by a combination of data from the Australian Maritime Safety Authority [under Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 Australia License] © AMSA 2013 and vessel positions inferred by the author based on social media posts. © AMSA 2013. Country data from Natural Earth Data.

Sources

Casarino, Cesare. “Modernity at Sea: Melville, Marx, Conrad in Crisis.” Theory out of Bounds, vol 21, 2002. University of Minnesota Press.

Foucault, Michel. “Of Other Spaces” (trans. Jay Miskowiec). Diacritics, vol. 16, No. 1, 1986. pp. 22-27.

Foucault, Michel. The Order of Things: An archaeology of the human sciences. Routledge. 2002.

Johanson, Oskar. “Degenerate Ark”. The Avery Review, Issue 39, 25 Apr 2019, http://averyreview.com/issues/39/degenerate-ark

Menagh, Joanna. “COVID quarantine breacher fined for escaping from Perth hotel room using bed sheets”. ABC News [Online]. 4 Aug 2021, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-08-04/man-fined-for-escaping-perth-hotel-quarantine-using-b ed-sheets/100349318

“The World's Biggest Cruise Ship”. Mega Food, directed by David Haynes. Nat Geo. 2013. Soja, Edward. Postmodern Geographies: The Reassertion of Space in Critical Social Theory.

Verso. 1989. pp.18-19.

Vidler, Anthony. “Heterotopias.” AA Files, No. 69, 2014. pp. 18-22. Architectural Association School of Architecture.

Author

Oskar Frederick Johanson (AA Dipl’19) is a designer, writer, and educator. He is co-director of the AA Visiting School Sydney and a course tutor at the Architectural Association. From 2020-21 he was a Research Fellow at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie. His work currently features in The Architecture of Staged Realities, an exhibition at Het Nieuwe Instituut, Rotterdam that opened in September 2021.

https://oskar.london

Utopian Thinking in the dark times – Spring/Summer 2022 Research Capsule by Neo-Metabolism – Editors: Georgia Kareola, Kavya Venkatraman, Nicholas Burman – Contributors: Felix Luke, Misha Kakabadze, Oskar Johanson, Nicholas Burman, Maithri, Frédérique Albert-Bordenave – Paintings: Eric L. Chen – Wordmark: Clint Soren – Site: dolor~puritan x cargo – Published: 1 March 2022